Unintended consequences have been reported to result from immigration restrictions. The introduction of the so-called 3- and 10-year bars, which impose harsh immigration repercussions on undocumented immigrants who stay in the US for lengthy periods of time, has wreaked havoc, separating families and – counterintuitively – incentivizing long-term illegal presence in the US.

While the bans on reentering the US for 3 or 10 years were designed to reduce the number of long-term unlawful residents, they have had the opposite effect, preventing migrants seeking short-term labor from returning to their home countries. Other facets of our immigration system are also distorted by the bans, which prevent many undocumented immigrants who would otherwise be eligible to modify their status from doing so and break up families.

The origins of the 3- and 10-year bars will be discussed in this paper. It will next look at the repercussions of their inception over 25 years ago, including how they are likely to have increased the number of undocumented immigrants in the United States and are threatening to keep families apart. Finally, this paper will consider reforms that could be implemented to solve these issues and establish a more equitable and successful immigration system.

Background

The IIRIRA (Illegal Immigration Reform and Immigrant Responsibility Act of 1996), which imposed new and enhanced punishments for immigration infractions in order to curb the expanding unauthorized immigrant population, established the 3- and 10-year restrictions.

Both restrictions are implemented in the same way; the only variation is the length of the penalty, which varies based on how long an individual has been in the United States illegally. The varied penalties are broken down in Table 1.

| Table 1: 3- and 10- Year Bar Penalties | |

| Penalty | Unlawful Stay in the U.S. |

| 3-Year Bar | At least 180 days, but less than 1 year |

| 10-Year Bar | 1 year or longer |

Periods of unlawful presence in the United States must be continuous in order for the bars to apply. In other words, the 3- and 10-year bars only apply once an unauthorized immigrant has been in the United States illegally for 180 days – they do not apply after repeated shorter stays. [1] Unauthorized immigrants who have been barred from entering the United States for three years must leave before removal proceedings can begin.

The 3-year ban does not apply, however, if the unlawful immigrant leaves the United States after removal procedures have begun. Unauthorized immigrants subject to the 10-year ban are free to depart the United States at any time before, during, or after their removal procedures are completed.

There is some ambiguity over where the bars should be served. The 3-year or 10-year bar begins upon expulsion or removal from the United States, although the Act does not specify where it must be spent. While most people serve their bar outside of the United States, there are some conditions in which the bar can be served while the owner is still in the country.

If an unauthorized immigrant gets paroled or permitted into the United States after leaving, or if they just rejoin the nation unlawfully, these are examples. According to a 2006 opinion letter from the USCIS Office of the Chief Counsel, if a previously barred individual re-enters the United States on a non-immigrant visa or on parole, the re-entry bar will only last for the duration of the visa or parole.

If the individual decides to stay in the United States illegally after his visa or parole has expired, the bar will remain in effect until he is removed from the country, at which point he will face a fresh re-entry bar. The re-entry bars would not be extended to anyone who illegally re-entered the United States as a result of this judgement.

However, because there are no formal rules on this subject, the decision on where either re-entry bar can be offered is made on a case-by-case basis. As a result, the Board of Immigration Appeals (BIA), the federal body charged with interpreting U.S. immigration law, has overruled previous USCIS rulings and declared in several cases that re-entry bars do not have to be served outside the United States, even if the individual illegally re-entered the country. However, USCIS has issued decisions stating that re-entry bars must be served outside the United States. The situation is still unresolved.

Effects and Consequences

The repercussions and impacts of the 3- and 10-year bars on the US immigration system have grown obvious in the 25 years after they were enacted. The effects are most visible in four areas: (1) the number of unauthorized immigrants in the United States, (2) their length of stay, (3) the number of immigrants who illegally overstay their visas, and (4) hurdles to family reunification. Each of these themes is discussed in detail below.

Unauthorized Immigrant Population in the United States Is Growing

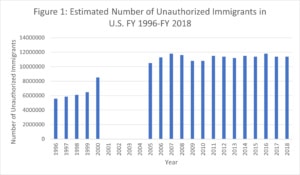

The 3- and 10-year restrictions were intended to assist prevent illegal immigration and disincentivize overstays as the unauthorized population grew from an estimated 3.5 million in 1990 to 5.7 million in 1995. The sponsors of IIRAIRA hoped that by imposing harsh penalties for unlawful presence, the bars would result in (1) a reduction in the number of unauthorized immigrants in the United States and (2) a deterrent to future unlawful immigration to the United States. The rise of the undocumented population after 1996, on the other hand, implies that the 3- and 10-year bars failed to achieve either purpose.

Source: Department of Homeland Security

Between FY 2001 and FY 2004, data was not available.

Following the establishment of the 3- and 10-year bars, the estimated illegal population in the United States increased significantly. Figure 1 depicts the increase in the number of undocumented immigrants in the United States since 1996, implying that the 3- and 10-year bans had little impact on reducing it, or were less substantial than other factors driving the increase. The estimated undocumented immigrant population in 1996 was 5.6 million; by 2007, it had more than quadrupled to 11.8 million, and has hovered around 11 million since then.

Is There a Reward for Staying?

Another interesting feature of the unauthorized immigrant population is that, as seen in Tables 2 and 3, they stay in the United States for longer durations of time on average. Between 1995 (just before the 3- and 10-year restrictions were enacted) and 2017, the percentage of undocumented immigrants in the United States for more than 10 years about doubled, while those in the country for less than 5 years nearly halved.

The median length of stay for undocumented immigrants more than doubled between 1995 and 2017, indicating a similar trend. This data also reveals that the three- and ten-year bans had minimal impact on the number of undocumented immigrants in the United States. In reality, it appears that unauthorized immigrants are choosing to stay in the United States for extended lengths of time because they are aware that if they leave, they will be barred from returning.

Instead of being a deterrent to individuals who intend to live unlawfully in the United States, the bars have become a major reason why unauthorized immigrants choose to stay in the country for longer periods of time, according to the research. These concerns also apply to undocumented immigrants who are qualified for a family-sponsored permanent residence visa, as waivers to excuse their illegal status are difficult to come by.

| Table 2: U.S. Unauthorized Adult Immigrant Population by Length of Residency | ||

| Year | 5 Years or Less | More than 10 Years |

| 1995 | 36% | 33% |

| 2000 | 38% | 35% |

| 2005 | 36% | 38% |

| 2007 | 30% | 41% |

| 2010 | 23% | 50% |

| 2015 | 17% | 64% |

| 2016 | 18% | 66% |

| 2017 | 20% | 66% |

| Table 3: U.S. Unauthorized Adult Immigrant Population Median Length of Residency | |

| Year | Number of Years |

| 1995 | 7.1 |

| 2000 | 7.2 |

| 2005 | 8.0 |

| 2007 | 8.6 |

| 2010 | 10.6 |

| 2015 | 13.9 |

| 2016 | 14.8 |

| 2017 | 15.1 |

Effects of Visa Overstays

A major driver of the increasing number of undocumented immigrants residing in the U.S. for longer periods of time has been the growth of visa overstays. Recent estimates suggest that more than half of undocumented immigrants in the U.S. are visa overstays.

Additional analysis has also indicated that overstaying a visa has become the primary method by which people become undocumented, as seen in Table 4. Government data between FY 2015 and FY 2019 suggests visa overstays have remained at high levels, indicating that the two bars are likely not serving as the deterrent factors they were originally envisioned to be.

| Table 4: Estimated Percent of the 2014 Undocumented Population that Entered the U.S. via Visa and Overstayed | |

| Year of Entry | Percent |

| 1995 | 29% |

| 2000 | 36% |

| 2004 | 37% |

| 2010 | 61% |

| 2014 | 66% |

| Table 5: Estimated Number of Visa Overstays FY 2015-FY 2019 | |

| Fiscal Year | Number of Visa Overstays |

| FY 2015 | 527,127 |

| FY 2016 | 739,478 |

| FY 2017 | 421,325 |

| FY 2018 | 666,582 |

| FY 2019 | 676,422 |

Barrier to Family Reunification

A final major consequence of the 3- and 10- year bars is that they break up families, especially mixed families consisting of one or more family members who are U.S. citizens or lawful permanent residents (LPRs, also known as “green card holders”) along with one or more family members who are undocumented.

Since those who are not present (or are not lawfully present) in the United States are required to apply for a green card from a U.S. State Department consulate abroad for an entry visa before adjusting status, those who attempt to do so may be barred from reentering the U.S. for years – even when these individuals already have established families and livelihoods.

However, by requiring individuals to leave the U.S. to attempt to obtain a green card, those who have unlawfully remained in the U.S. for extended periods are barred from reentering. With limited alternatives, many families face terrible dilemmas. These punitive measures have led many unauthorized immigrants either related to or married to U.S. citizens or LPRs to not adjust their immigration status, even when otherwise eligible to do so.

It is estimated that the 3- and 10- year bars are preventing around 1.2 million spouses of either U.S. citizens or LPRs from acquiring green cards.

Inadmissibility Waivers

While the bars disqualify tens of thousands of people from applying for a visa, there are a few inadmissibility waivers through which inadmissible noncitizens can come legally to the U.S. The waivers, however, are discretionary and do not guarantee relief to all applicants.

To apply for an inadmissibility waiver, applicants must demonstrate sufficient family and community ties to the United States. If an applicant meets all other statutory and regulatory requirements of the waiver, consular officers must determine whether to approve the waiver as a matter of discretion.

Nevertheless, meeting the statutory and regulatory requirements alone does not entitle the applicant to relief.

The applicant bears the burden of proving that he or she merits a favorable exercise of discretion. The approval of a waiver depends on whether the positive social factors and humanitarian considerations in the applicant’s case outweigh the unfavorable ones.

For instance, demonstrating honorable service in the U.S. armed forces, having property or business ties in the U.S., or being the primary caretaker of a terminally ill U.S. citizen or LPR relative can improve the chances of getting a waiver.

Granting waivers, however, rely on the discretion of consular officers, and it can take months to get a final resolution.

Possible Reforms

Rather than reducing unauthorized immigration, the 3- and 10- year bars have had unforeseen consequences that have increased the undocumented population and kept families apart. Congress should act to make reforms to mitigate the negative impacts of the bars or eliminate them entirely.

Eliminate the 3- and 10-Year Bars

Eliminating the bars would be the most straightforward method to address the bars’ negative consequences. President Biden on his first day in office sent Congress an outline of the U.S. Citizenship Act of 2021, which among many reforms would eliminate the 3- and 10- year bars. However, as of the date of this paper’s publication, the bill has not received floor votes in either the House of Representatives or the Senate.

Reinstate Section 245(i) Adjustments

Reinvigorating Section 245(i) adjustments is another way to mitigate the harms created by the 3- and 10-year bars. Section 245(i) is the part of the Immigration and Nationality Act (INA) that allows certain unauthorized immigrants to adjust their immigration status without having to leave the U.S. along with paying a $1,000 penalty.

Created in 1994 and further amended by the Legal Immigration Family Equality (LIFE) Act, the adjustment currently only applies to those unauthorized immigrants who had an employment or family-based visa filed on their behalf prior to April 30, 2001.

Consequently, there are exceedingly few cases currently where this adjustment can be applied. Although Congress has the power to extend or eliminate the current 2001 deadline, it has not done so.

If Congress were to extend or eliminate the deadline, as in recently proposed legislation such as the Fairness for Immigrant Families Act, an estimated 2.3 million unauthorized immigrants could become eligible for an adjustment of status and placed on a path to acquiring legal residency.

Reduce the Time Penalty of the Bars

If eliminating the 3- and 10- year bars entirely proves to be politically impossible, reducing the time penalty of the bars or scaling the time penalties to correspond to the severity of the immigration offense or public threat would be an attractive alternative.

These reductions would bring the U.S. in line with other destination countries, which maintain bars to reentry, but for shorter periods of time. For example, Canada bars unauthorized immigrants from re-entry for one year, Australia does so for up to three years.

The Netherlands and Germany both have multiple reentry bars depending on additional aggravating factors, with longer bars applying for those who pose serious risks to public safety or national security – not just unlawful presence. Additional details can be seen in Table 6.

| Table 6: Bars to Re-entry Policies of Other Migration Destination Countries | ||

| Country | Time Spent Illegally in Country/Qualifying Condition | Bar to Re-entry Length |

| Canada | N/A | 1 year for majority of offenses |

| 5 years for misrepresentation | ||

| Australia | 28 days or more | Up to 3 years |

| Netherlands | 3-90 days | 1 year |

| Over 90 days | 2 years | |

| Risk to public order | 10 years | |

| Risk to national security | 20 years | |

| Germany | Expelled, removed, or deported | Up to 5 years |

| Criminal conviction or threat to public safety | Up to 10 years | |

| Risk to national security | 20 years |

Conclusion

The 3- and 10- year bars were originally designed to deter future illegal immigration and to decrease the undocumented immigrant population. However, they have failed on both counts and likely served to increase the undocumented population by discouraging those with unlawful presence from leaving the U.S.

The 3- and 10-year bars have kept families apart and prevented immigrants otherwise eligible to adjust immigration status from doing so, undermining and distorting an already over-complicated U.S. immigration system.

Until reforms are made to address the 3- and 10-year bars, these problems will continue. Congress should act to eliminate the bars, create exceptions like Section 245(i), or at least reduce the time penalties in order to end a failed policy. Doing so will open opportunities for hundreds of thousands of otherwise eligible immigrants to apply for and receive legal status in the U.S.

The bars do not apply to minors under 18 years of age, even if they have unlawfully resided in the United States.

Legal Help from Hindieh Law

Hindieh Law found that this “The Need to Reform or End the 3- and 10-Year Bars” article from National Immigration Forum is interesting and good to know for everyone.

If you or a family member have a complicated Crimmigration issue that you would like help with, call 214 Release: Hindieh Law, PLLC at 214-Release (214.960.1458) for a free confidential consultation today.

Hindieh Law is a trusted servant to the Hispanic and Latino communities helping families gain their loved ones back to the U.S. and keeping them here in the U.S. during the immigration process if there are pending criminal charges.

The merger of complicated immigration law and criminal proceedings is a special area of the law called “Crimmigration.” Hindieh Law is a Crimmigration specialist and is well respected by Hispanic & Latino families.